Translated fiction: What’s the story?

Korean novel The Vegetarian, a dark tale about a woman who decides to stop eating meat and become a tree, was last week awarded the coveted Man Booker International prize, which is shared equally between its Korean author Han Kang and its English translator, Deborah Smith. With the popularity of translated fiction ever on the rise in the UK and even selling better than non-translated fiction, we got thinking about the specialist field of literary translation and about our favourite translated novels.

Translating novels presents its own challenges, which can place it squarely on a par with technical translations on the difficulty scale. The literary translator faces a huge amount of decisions, being ultimately responsible for what can be seen as the holy grail task of re-producing the same effect the original had on the new target readership. For this to even be possible, a brilliant mix of sound knowledge of both the source and target culture and context, flawless command of their native language, and great confidence to make bold decisions is required.

Understanding the author and their intentions

The fiction translator needs to really get inside the author’s head. This means reading and re-reading the novel to recognise the style, nuance, context and any different interpretations. It also often means collaborating closely with the author themselves and with publishers. It seems to be in this respect that Deborah Smith’s translation of The Vegetarian was so successful – she has been praised for maintaining the many different interpretations of the story intended and hinted at by Han Kang.

Another novel with many different interpretations is my favourite translated book, Franz Kafka’s Die Verwandlung (The Metamorphosis). A tale about a young man who wakes up to find himself transformed into “Ungeziefer” (a general term for a “bug” of sorts), the many different English translators who have tackled it must have struggled not only with how to translate “Ungeziefer” itself (as vermin, bug, insect, bedbug, among others), but also with the many different meanings and interpretations Kafka intended to evoke through his writing. For me, the best translated version is by Christopher Moncrieff, who takes the novel on in a very idiosyncratic way.

Evoking the same response in the new readership

At the same time as getting inside the head of the author, the successful literary translator must squarely position themselves in the new reader’s shoes, writing in a way that stirs the same emotions and feelings for them as it does for the readers of the original. After having a discussion about our favourite translated novels in the office, Anja said she feels that the English translation of Der Schwarm (The Swarm) by Frank Schätzing is very successful in this respect. A novel carrying an important message about the destruction of marine ecosystems, the story follows a group investigating freak events on the world’s oceans. Having enjoyed the German original so much, Anja read the English translation, and felt that the translator, Sally-Ann Spencer, did a great job of capturing and evoking the same emotions she felt the first time round.

Translating confidently and creatively

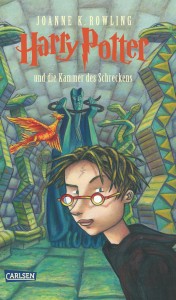

With this aim of achieving the same effect in the new readership, the literary translator needs a creative mind, confidence and also needs to grant themselves a great deal of freedom. The French and German Harry Potter translations, which had a big impact on both Daniel and Cassandre growing up, are prime examples. The translators made J.K. Rowling’s magical, exciting world full of wordplay fully accessible and did a great job taking the freedom to localise the names and places that were full of meaning. For instance, French Harry Potter translator Jean-François Ménard coined the French name for Hogwarts school, “Poudlard” (inferring “poux-de-lard” which means “bacon lice”) and also Severus Snape’s surname, “Rogue” (meaning ‘haughty’), among dozens of other inventions. Without such confident translations both the humour and Rowling’s attention to the detail would have been lost. Elsewhere, the German translator Klaus Fritz’s translation is a very idiomatic read. Where he was unable to replicate wordplay, such as with the name “Diagon Alley”, translated simply as “Winklegasse” (Corner Alley), he instead strove to reproduce the same flow of wordplay in the novel as a whole, sometimes inventing new jokes to make up for any that were lost in translation.

Loving what you do

Literary translators need a great deal of passion and perseverance, and to be prepared for many drafts and re-drafts. It is certainly a very rewarding branch of the translation industry. Thanks to literary translators, the inaccessible becomes accessible for us all to enjoy. As acclaimed Italian writer Italo Calvino said:

“Without translation, I would be limited to the borders of my own country. The translator is my most important ally. He introduces me to the world.”